The FPSO Industry and Top-Tier Lessor and Operator - Yinson

26 September 2023

What is FPSO?

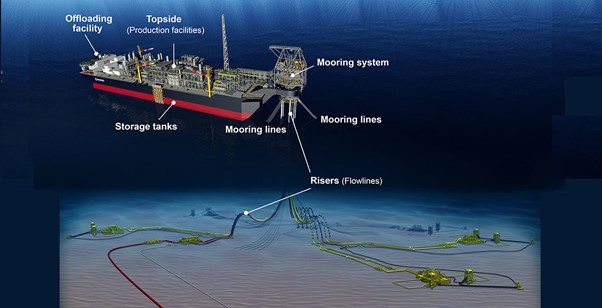

FPSO stands for Floating, Production, Storage and Offloading. It is a floating production system that receives fluids (crude oil, water, and a host of other things) from a subsea reservoir through risers (think of “pipes”), which then separate fluids into crude oil, natural gas, water, and impurities within the topsides production facilities onboard. Crude oil is stored in the storage tanks of the FPSO which is then offloaded onto shuttle tankers. Gas is typically used as fuel in the turbine or reinjected back into the well.

A vessel used only to store oil (without processing it) is referred to as a floating storage and offloading (FSO) vessel.

Most FPSOs/FSOs are ship-shaped and can be secured to the seabed via a variety of mooring systems, the choice of which is determined by the specific environment. They are suitable for a wide range of water depth, environmental conditions and can be designed with the capability of staying on location for continuous operations for 20 years or longer.

Large FPSOs have mainly been based on converting used Very Large Crude Carriers (VLCCs) in recent years. A small percentage of FPSOs are newly build, meaning the hull is new as compared to using an existing tanker do conversion. It is faster to do conversion, which could take around 2 years as compared to new build which may need up to twice the amount of time. The drawback of converting existing tanker would be less space for topsides and hull integrity could be a concern if the converted FPSO is expected to operate for more than 20 years.

The world’s first FPSO was introduced in 1977, on Shell’s Castellon field (FPSO Delta) in the Spanish Mediterranean. It was a converted tanker vessel that had been modified to accommodate the necessary production and storage facilities. It featured a turret mooring system (supplied by SBM) that allowed it to rotate around a fixed point and remain stable in rough seas. It could produce 60,000 barrels of oil per day and storing up to 1 million barrels of oil. There are currently 167 FPSO vessels deployed worldwide, with 35 more under construction and 16 idle.

Topside, hull and mooring system are the three key components of an FPSO. The hull can be either converted from an existing tanker or newly built, and is typically built or refurbished in China or South Korea. In the past, most FPSO lease contractors developed their own mooring systems, which were considered proprietary technology. However, there are now independent mooring system providers available.

The topside processing facilities include many equipment such as crude oil/gas separation and conditioning packages, turbines, generators, hydraulic power unit, various types of pumps, seawater injection package, carbon dioxide removal system, accommodation module etc.

Given that each oil & gas field may differs in terms of production scale, chemical contents, gas to oil composition, CO2 emission standard, weather condition, etc., each FPSO needs to be designed to match the project-specific conditions. We may think of it like a custom-made floating factory with storage tanks.

Why use an FPSO?

Oil production from offshore locations began in the late 1940s. Initially, all oil platforms were fixed to the seabed. However, as exploration moved to deeper waters and more distant locations in the 1970s, floating production systems were introduced.

There are two alternatives to an FPSO unit: a fixed platform or seabed pipelines. FPSOs have several advantages over these alternatives. First, they can be used to developed marginal oil field where a few years of operation do not justify installation of pipelines or fixed platform. It could be redeployed to a new marginal field once the existing field is depleted. This is not possible with fixed platforms, which are permanently moored to the seabed and carries high cost of abandonment.

Second, FPSOs are particularly effective in remote or deep-water locations, where seabed pipelines are not cost effective. Typically, FPSOs become more cost-effective than fixed platforms at water depths greater than 400 meters.

Process of building an FPSO

Front-End Engineering Design (FEED) - Front-End Engineering focuses on technical requirements and identifying main costs for a proposed project. It is used to establish a price for the execution phase of the project and evaluate potential risks. Benchmark studies have shown that FEED constitutes roughly 2% of the project cost but properly executed FEED projects can reduce up to 30% of costs during design and execution.

Bidding, negotiation, and contract award.

Detail design engineering, sourcing, project management and construction. Construction usually can be broken down into two parts:

- Building/refurbishment of hull – Usually the hull is built/refurbished in a China shipyard such as Dalian Shipbuilding Industry, Cosco Shipping Heavy Industry, Shanghai Waigaoqiao Shipbuilding etc.

- Integration work – The completed/refurbished hull would be sent to shipyard that specializes in integrating all the topsides module. Usually such works are carried out by Singapore/Korea shipyards such as Daewoo Shipbuilding and Marine Engineering (DSME), Hyundai Heavy Industries (HHI), Samsung Heavy Industries, Seatrium (Combination of Sembcorp Marine and Keppel Shipyard). In recent years, Chinese yard such as CIMC Raffles, BOMESC and China Offshore Oil Engineering Company (COOEC) also started doing integration work.

The completed FPSO will then set sail for the oil field and get hooked up and commissioned. The FPSO lease contractor will focus on achieve final acceptance and after which, it will entitle to full day rate payment and the loan will no longer be recourse to the lessor.

Business model of FPSO suppliers

Generally, there are 3 business models in the FPSO industries, which are:

- Full Engineering, procurement construction and Installation (EPCI) Basically the oil company gives out the contract to build the FPSO and make payment according to construction progress. Some full EPCI vendors will need to outsource the FEED and detail design engineering to third party firms such as Technip or Ranhill-Worley. It also acts as the main contractor to ensure the project is completed on time and within budget. It does not need the financing capacity to own the FPSO.

However, it should be noted that it is getting harder to come up with a good FPSO design without operational experience. Furthermore, technological advancement such as digital twin and low-emission FPSOs, which are being led by FPSO lease contractors, have made it more difficult for general EPC contractors and shipyard to enter this market.

- Charter contract (Build, own and lease under long term contract which typically consist of a firm and an option period.) –

Oil companies typically put out tenders for FPSO lease contractor to submit their designs and pricing. The oil companies usually pay the bidders upfront for the cost of designing the FPSO, which can be a few million US dollars. Given that FPSOs are highly complex and customized vessels, it can take a large team of 20-30 engineers several months to complete the design.

After winning the bid, the FPSO lease contractor will build the FPSO and deliver it within the agreed-upon timeframe. The lessor will be responsible for financing the construction and ownership of the FPSO. However, after final acceptance and release of performance guarantee by the client, the loan will become non-recourse to the lessor and will instead be guaranteed by the oil company through the novation of guaranteed lease payment. If the lease is terminated, the oil company must pay a termination fee which normally equals to all remaining rentals based on the firm period of the contract. The termination fee would cover all the FPSO's debts and profits.

There are two types of charter contracts: bareboat and time charter. In a bareboat charter, the oil company operates the vessel itself. In a time charter, the lessor provides the crew and operates and maintains (O&M) the vessel for the duration of the contract.

- Build, operate, transfer (BOT) Basically, this is an EPCI contract with a short period of ownership and operation and maintenance (O&M) by the contractor before transferring it to the oil company. The purpose is for the contractor to operate and stabilize the performance of the FPSO for a year or two after delivery to ensure that everything is working properly.

Lease vs. Buy

From oil companies point-of-view, normally it is cheaper to buy (EPCI) than is to lease (charter) an FPSO. However, there are additional considerations to take into account when deciding whether to buy or lease, such as:

Most oil companies do not have a large project management team or the right FPSO design and engineering team, as they do not need them very often. Some of the FPSO lessors with strong design and engineering capabilities are not interested in doing EPCI jobs.

Typically, FPSO lessor only gets paid when the FPSO achieves first oil and fulfil the uptime threshold. Oil companies do not take any construction or project management risks. It should be noted that majority of FPSO jobs are delivered late.

For an EPCI job, oil companies must make a downpayment and pay based on the progress of the work. They also need to manage the EPCI contractor. If there is a major issue, the oil company may have already paid a large sum of money and cannot cancel the contract.

For oil company such as Petrobras and Exxon that need multiple FPSOs, one of the reasons to lease is to get a benchmark for their own FPSOs job.

Normally, FPSO lessor will be engaged to provide O&M over the lease period of say 20 years. It must maintain certain operational uptime and stringent HSE requirement. It means that when it was designing and building the ship, it would want to ensure that the equipment used (valves, pumps etc) is of good quality and can last that long. It has vested interest to ensure it perform well over the entire contractual period.

For an EPCI contractor, their job is to build and deliver an FPSO within a certain timeframe, based on the design provided by the client. It is not their primary goal to question the design or to ensure that the equipment will work well for the next 20 years.

Risks

There are 4 major risk areas in the FPSO business:

- Counterparty

Given the high capex and long-term nature of the lease period, you only want to do business with counterparty who will survive the worst downturn of oil cycle. As mentioned, if an FPSO is terminated during the firm period, the lessee (oil company) must pay termination fees equal to the remaining charter rental. Risk of force majeure events are also borne by oil companies. Just like any business, management needs to know when to say no and it is a matter of management’s discipline in selecting the strong counterparty to do business with.

FPSOs are essentially floating oil factories. For large oil fields, the average cash production cost per barrel is only a few US dollars. All the exploration and subsea assets invested are sunk costs, so even if the oil price drops to US$30 per barrel, it still makes sense for oil companies to continue producing oil, as the variable cost is less than US$10 per barrel. This is why we have historically seen very few cancellations of FPSO contracts, even when oil prices are low. Terminations usually happen when the productivity of a field turns out to be much lower than the initial estimate, and this risk is borne by the oil companies.

- Project management and execution

Building an FPSO is a complex project that involves sourcing from hundreds of suppliers and coordinating them with the shipyard to integrate the components. Late delivery can be very costly, with liquidated damages potentially running into hundreds of thousands of dollars per day. Even more important is the quality of the work, which will affect the uptime and safety of the FPSO for many years to come. In fact, most FPSO projects are delivered late, and many contractors and lessors lose money as a result. Consistent project execution and on-time delivery are clear indicators of strong project management capabilities.

- Contractual term

Contractual terms are often the result of negotiation and bargaining power. A good FPSO operator will negotiate for the most favourable terms possible, such as a lower local content requirement, a longer firm period, and a favourable termination clause. This will give the operator more flexibility and protect their investment in the event of unforeseen events.

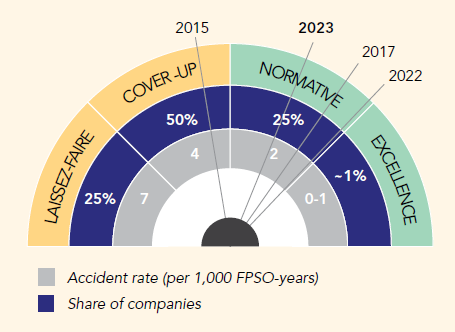

- Health & Safety/Operational risk

Over the past decade, there had been several reported incidents of fire, oil leaks, and explosions involving FPSOs. Some of these incidents have resulted in loss of life, and all of them have led to significant financial losses and extended downtime. A strong health and safety track record is essential for any FPSO operator, as it reflects a commitment to safety culture and strict operating procedures.

Operational wise, FPSO is designed to have high uptime to produce oil consistently. Failure to do so could result in substantial penalty.

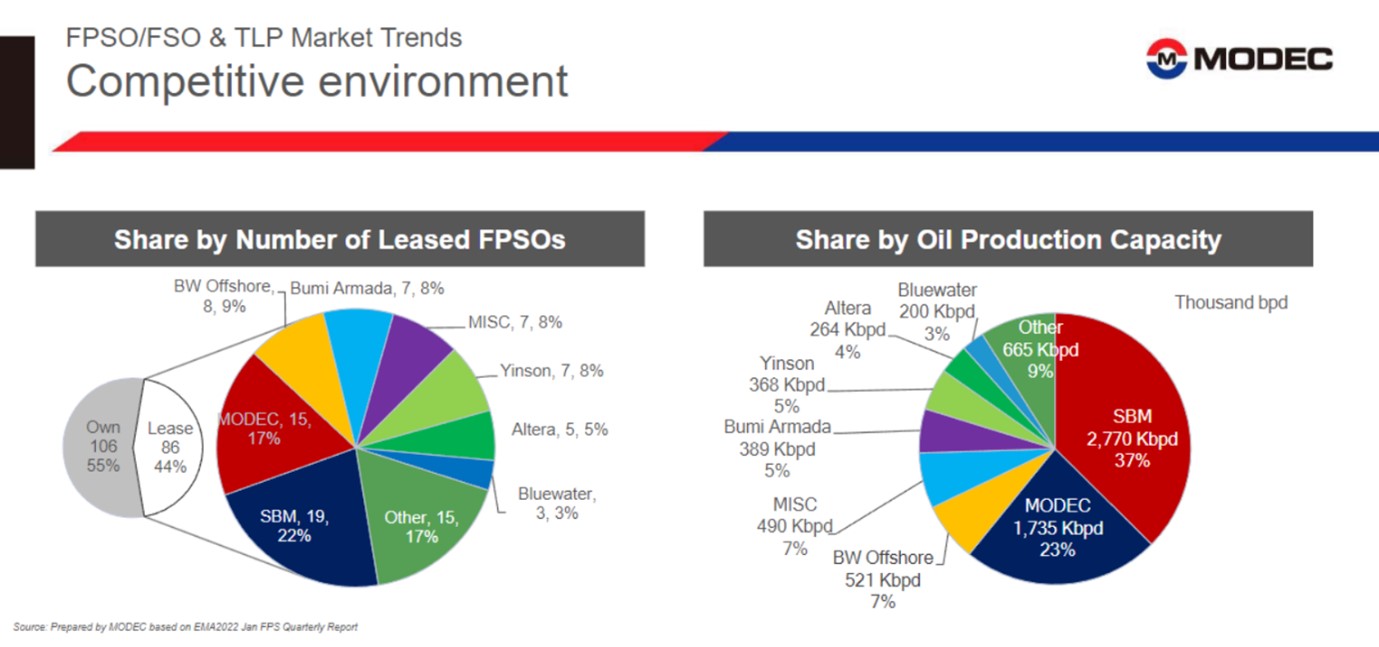

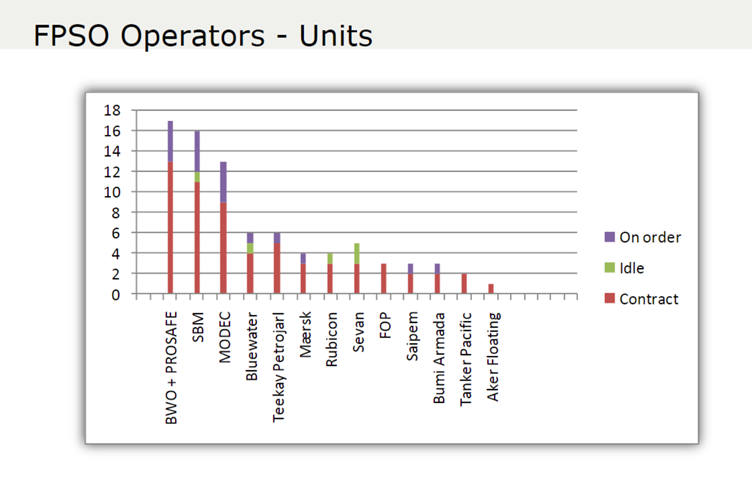

Main FPSO lease contractors in the industry

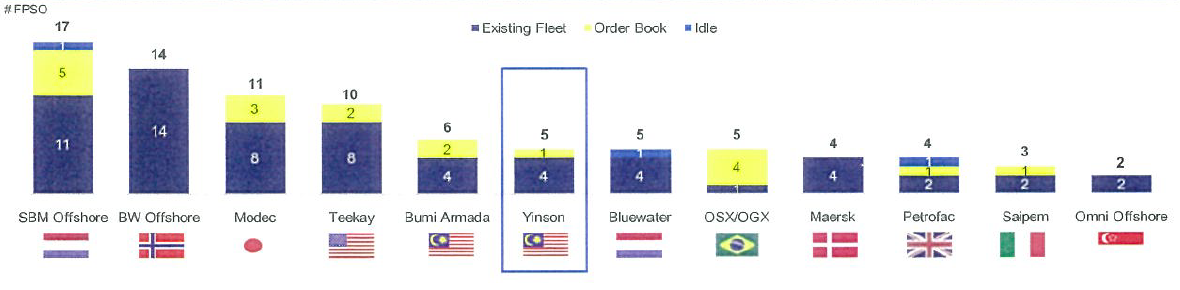

2014

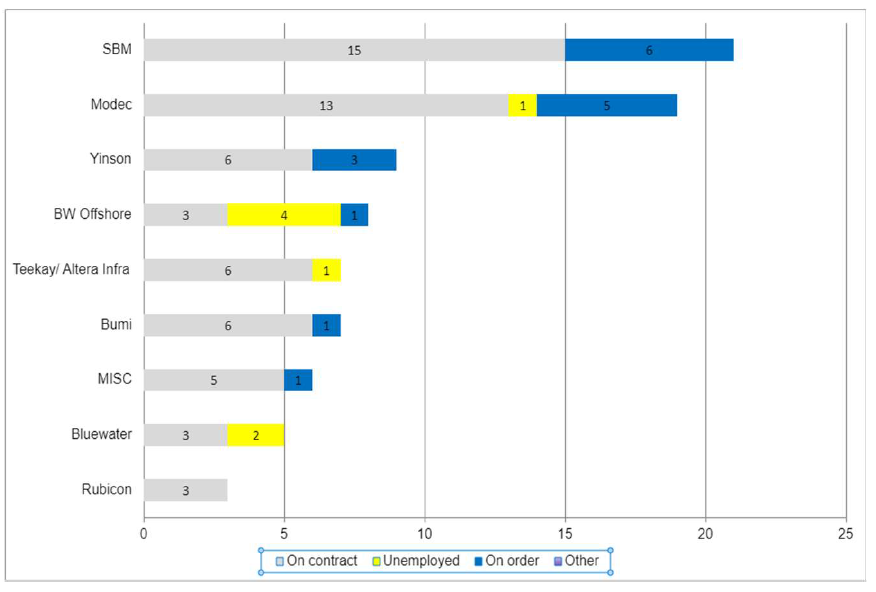

2023

The number of FPSO lease contractors that are still actively participating in new projects has decreased from 30 to less than 8 since the Global Financial Crisis of 2008. To be considered active, a lease contractor must have a design and engineering team, project management team as well as the financing capacity to take on new projects.

While there have been several lease terminations after the oil price collapse in 2014, in most cases, the early termination fees were paid in full. Low oil prices are only one of the reasons why FPSO players may exit the market or lose their financing capacity to take on new projects. Other important reasons include project delays, failure to meet uptime requirements, and health, safety, and environmental (HSE) issues.

Here is a summary of some incidents (not exhaustive) in the past decade:

- SBM Offshore (Netherland) – capacity: 2 FPSOs per year

As mentioned, SBM supplied the turret mooring system to the first FPSO in the world. It subsequently became a pioneer in single buoy moorings (SBM) systems. In the initial years when mooring technology is considered proprietary, SBM leverages to become the largest FPSO vendor/owner in the world.

SBM expanded into MOPU (mobile offshore production unit) business in 2000s. Its attempt in building MOPU STOR for the YME field experienced massive delay. The newly installed YME MOPU STOR was abandoned and decommissioned without having entered production due to platform structural safety issues. A separate attempt to build a MOPU for Deep Panuke field also experienced massive delay. Between 2009 and 2014, these two units resulted in an aggregate impairment loss of USD 2.4bn.

Between 2014 and 2017, SBM made legal settlement totalled USD 750m to Dutch, US and Brazil government. These settlements are related to several potentially improper sales payments and corruption charges.

Its FPSO Cidade de Anchieta shut down in Jan 2022 when oil was observed close to the vessel and the company incurred an impairment of USD92m. The FPSO safely resumes production in Dec 2022.

New CEO Bruno Chabas took over the rein in 2012 and refocus the companies back to its core FPSO business. The new management stated, “change management is a key success factor”. To be fair, the project execution since then has been decent besides some delays due to covid-19. SBM has also stated that it will not take more than 2 large FPSO jobs each year.

- MODEC INC (Japan) – capacity: 2 EPCI jobs per year; if it is lease – maybe just 1 per year

MODEC, the world's second largest FPSO player, had a successful run since its listing in 2003. However, in 2018, the company experienced a series of setbacks, including a hull crack on the FPSO Cidade do Rio de Janeiro in Brazil that led to an oil spill. The COVID-19 pandemic and operational issues also caused extended downtime for some of its other FPSOs in Brazil. As a result of these issues, Petrobras suspended MODEC from participating in new competitive bidding for 13 months from March 31, 2021.

In late 2019, MODEC had 6 new sizable FPSOs jobs in hand. However, the COVID-19 pandemic and the movement of project personnel contributed to cost overruns, project delays, and significant impairments between 2019 and 2022. The company's aggregate losses from impairments and repair work over this 3-year period were at least USD750 million.

- BW Offshore (Norway) – capacity: 1 FPSO every 2-3 years

BW was the second-largest FPSO player back in 2014, with 14 active FPSO leases. This has since decreased to 3 active leases, 1 under construction, and the rest sold or decommissioned.

Since 2008, BW has recognized several major impairments of the residual value of its vessels due to the non-exercise of optional periods and terminations. Unfortunately, an accident occurred on the FPSO Cidade de São Mateus (gas explosion) in 2015, leading to an impairment of close to USD500 million. The aggregate impairment that BW has recognized since 2008 amounts to USD1.8 billion.

As mentioned, BW has been downsizing its operations since then. It currently has 1 large FPSO under construction since 2021. It was expecting to receive one new FPSO job from Shell for the Gato do Mato field, but Shell has delayed the final investment decision.

After experiencing several major impairments, delays, and terminations over the past decade, BW Offshore has established clear selection criteria for new offshore oil and gas production projects. These criteria target infrastructure-type projects with:

- Firm contract periods of more than 15 years.

- Project execution and co-investing with partners.

- Solid national energy companies (NECs) and investment-grade counterparties.

- Yinson (Malaysia) – capacity: 1 FPSO a year

Yinson is the only FPSO company that has consistently turned a profit over the past decade. It has a proven track record of delivering FPSO projects on time and within budget, even during the COVID-19 pandemic, when it was the only company in the world to not delay a project due to the pandemic. Yinson has also had no major health, safety, or environmental or downtime incidents. As a result of its strong track record, Yinson is a preferred bidder in the market.

The company has experienced several contract terminations in the past decade, and it has received termination fees in each case. Here is a summary of the terminated contracts:

FPSO Lam Son - The FPSO was originally supposed to be leased until June 2021, but the lease was terminated early in April 2017 due to lower production levels than expected. Yinson was paid termination fees. The client continued to charter the FPSO to work at the same field at a lower day rate. The FPSO has recently been extended until June 2024, with an automatic 6-month extension until December 2024.

FPSO Knock Allan – The FPSO was originally supposed to be leased until April 2019, but the lease was terminated in late 2018. It had previously operated for nearly 10 years in the Olowi Field in Gabon for Canadian Natural Resources before the field ran dry. Yinson was paid the termination fees. The FPSO was upgraded and redeployed as FPSO Abigail-Joseph to Nigeria under First E&P in 2020 on a firm seven-year contract.

Repsol’s Ca Rong Do – In 1Q18, Yinson’s JV PTSC Ca Rong Do was notified by Repsol of a force majeure event (Vietnam’s territorial dispute with China). The upgrading contract for the vessel has yet to be awarded at that time. Yinson's JV has finalized a full compensation deal for the contract termination in 2020.

FPSO Pecan Letter of Intent (LOI) – Aker Energy and Yinson entered a letter of intent (LOI) for the provision of an FPSO vessel for the Pecan field. However, the LOI was terminated in early 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic and low oil prices. Yinson has been compensated for the work that was already completed.

In two of the four cases, Yinson was compensated for the termination of existing leases, and in the other two cases, it was compensated for the termination of contracts for vessels under construction. This shows that Yinson has chosen its counterparties carefully and that its contracts are well-written, with strong provisions for termination.

- Altera Infrastructure LP (formerly known as Teekay Offshore Partners LP) – working on redeploying 2 idle FPSOs – limited capacity to take on new job

In 2017, Brookfield Business partners LP completed a USD640 million equity investment in Teekay Offshore for 60% stake. In 2019, Teekay Corp sold all remaining interests in Teekay Offshore to Brookfield for a further USD100 million, signalling their exit from the FPSO space.

Altera experienced financial difficulties and filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection in 2022. It emerged from Chapter 11 in January 2023 with a restructured balance sheet and a deal to redeploy its idle FPSO Petrojarl Knarr to Equinor's Rosebank field. However, its last FPSO was built in 2014, and it is unclear whether it still has the design and engineering team in place to take on new jobs.

- Bumi Armada (Malaysia) – limited financing capacity to take on new lease contract

Bumi Armada was doing well until the collapse of oil prices in 2014. The oil price crash exposed some of its customers as not being as financially sound as they seemed, and it began to record impairments on its trade receivables. Multiple project delays and terminations have resulted in an aggregate impairment of over RM5 billion since 2014. This includes approximately RM1.8 billion for the FPSO Armada Claire and RM1.6 billion for the FPSO Armada Kraken.

The FPSO Armada Claire was delivered to the Belnaves field in 2014 but did not achieve final acceptance. In 2016, Woodside terminated the contract for the FPSO, citing "performance-related issues." This may have been coincidental, but it also happened to be a time when oil prices were low and the Belnaves field was experiencing a sharp production decline. Bumi Armada challenged Woodside in court but lost the case in 2022.

The FPSO Armada Kraken was impaired due to project delays, underperformance, and low uptime availability.

In 2017, Bumi Armada suspended the operations of FPSO Armada Perdana following irregular payments for the operation and maintenance services, together with long-delayed charter by independent oil and gas operator Erin Energy Corp, which filed for bankruptcy shortly after.

In the last 6 years, it has only secured one new FPSO job, with a 30% stake. This suggests that the company may have limited design and engineering capacity, as well as financing capacity, in the near term to take on sizable jobs.

- MISC - capacity: unknown given the current job is being delayed

MISC did not take on any new FPSO projects for five years after the delivery of the MAMPU 1 FPSO (a small one with 10k barrels per day of capacity) in 2015. In late 2020, it secured the Mero 3 FPSO project, which is a large FPSO with a production capacity of 180k barrels per day. However, the project has been delayed by at least six months to mid-2024 and is experiencing cost overruns caused by the Shanghai lockdown and global supply chain issues.

It appears that the company is unlikely to take on new job until Mero-3 is completed.

- Bluewater – focus on redeploying its idle asset. Low likelihood to take on new job

Bluewater has 5 FPSOs units, 2 of which are idle. All the FPSOs were built between 10 and 20 years ago. The company’s current focus is to redeploy the idle units and is unlikely to take on any sizable jobs soon.

9 Rubicon – it is exiting from FPSO business.

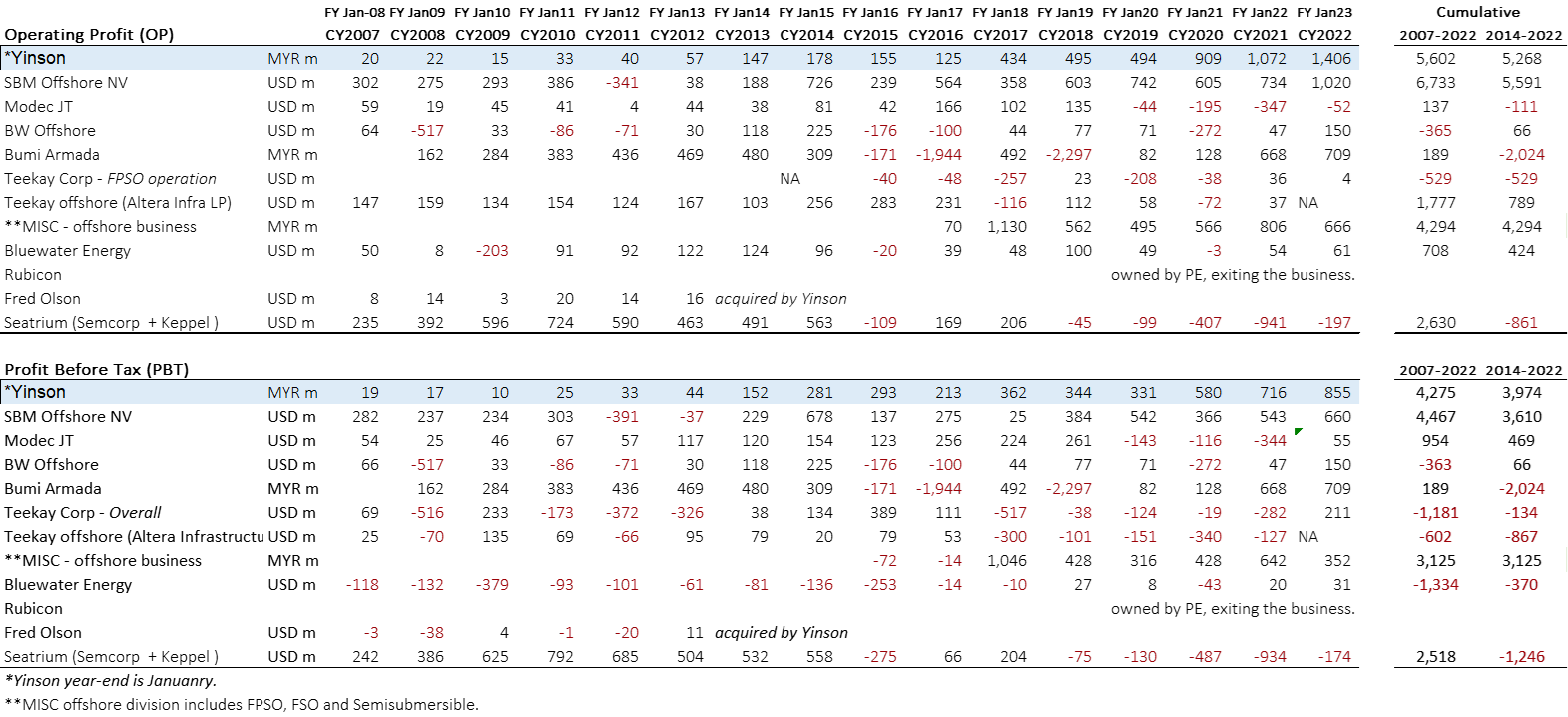

Financial performance of main FPSO players

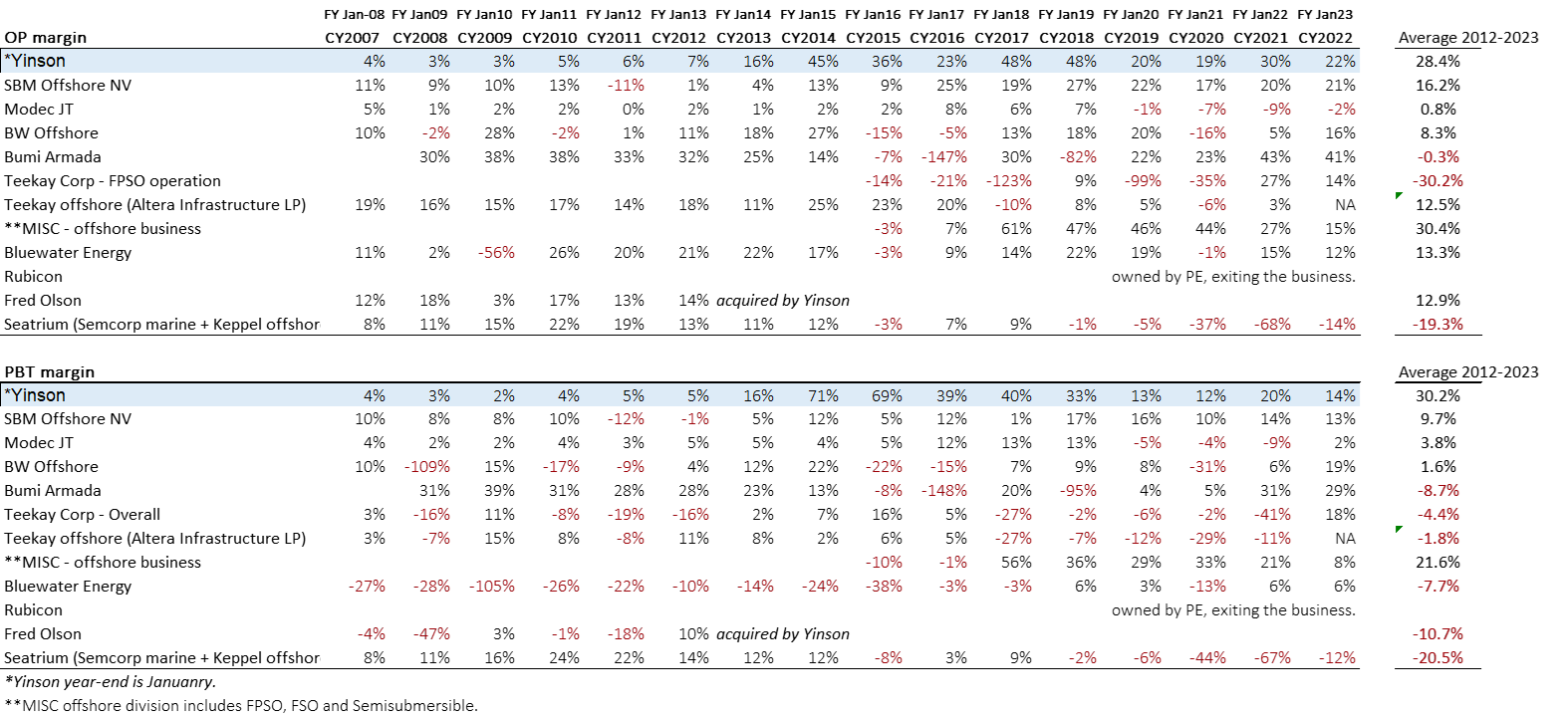

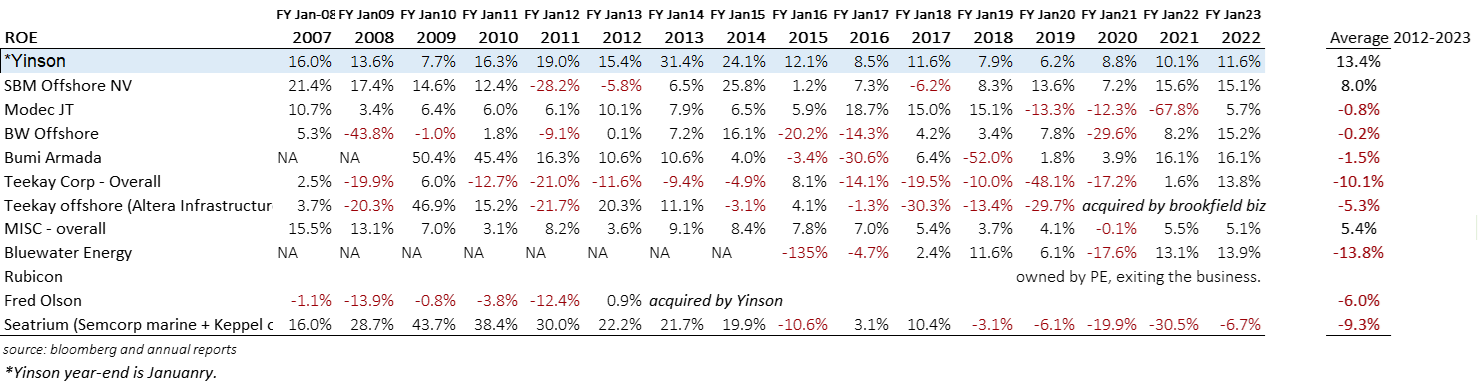

Yinson is the only FPSO lease contractor that is consistently profitable throughout the period. SBM has done quite well since 2014 if we exclude the litigation settlement with government. Modec did well until 2019 but then lost money for three years. It has recently returned to profitability in the recent quarter. Bumi Armada has also returned to profitability after several years of massive impairments, but its balance sheet and financing capacity are not yet fully restored. Seatrium is an integrator yard that also takes on full EPC jobs, and it has been bleeding for several years.

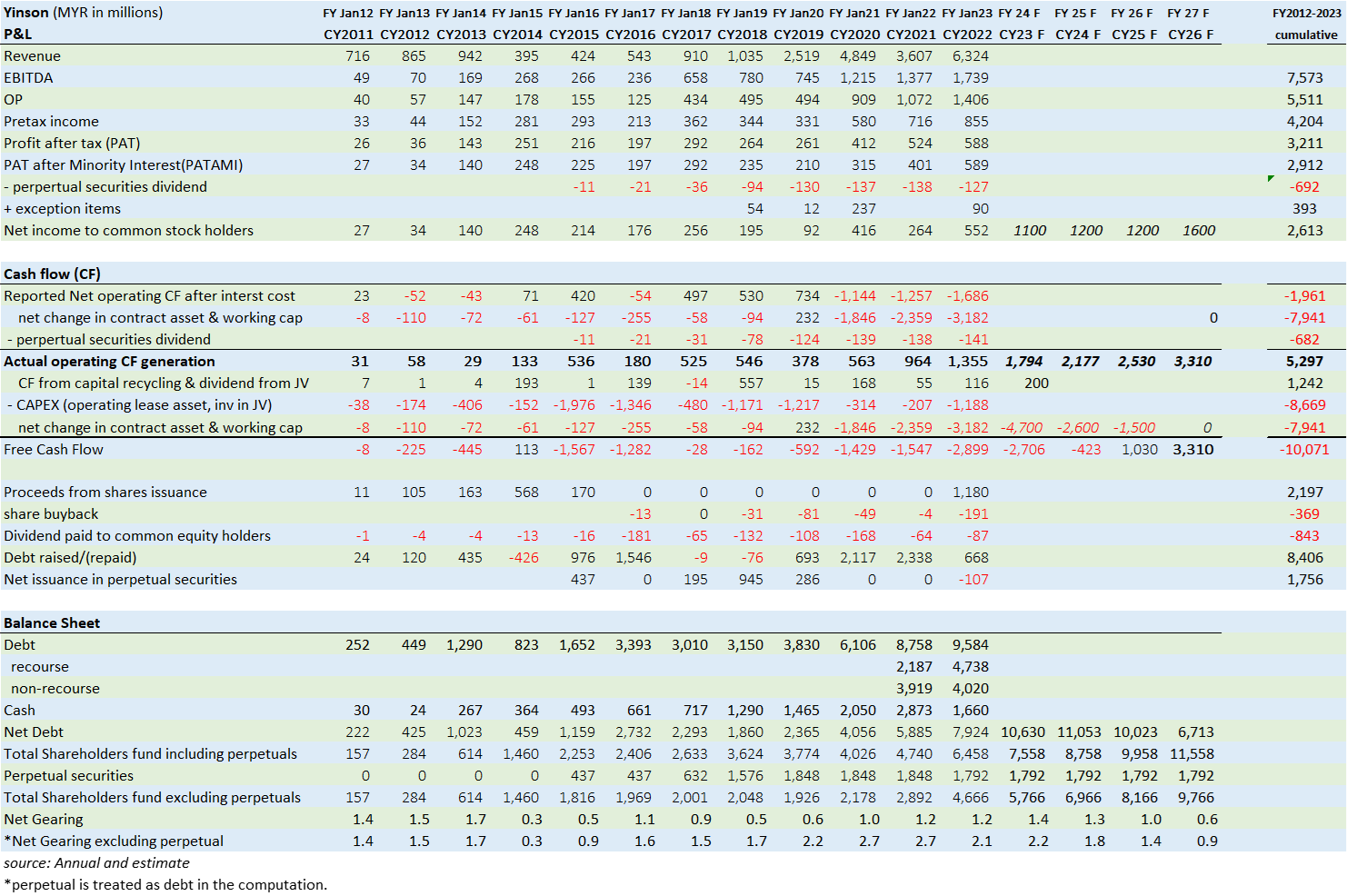

Yinson entered the offshore oil production industry in 2012 and its margin has been increasing since then. However, the average margin in the last four years is lower than the previous years due to the accounting treatment of finance leases. Under finance lease accounting, Yinson is required to recognize construction revenue and profit during the construction phase, which lowers the company's margin. Once these FPSOs start operation, Yinson's margin should start moving up again.

Only Yinson, SBM, and MISC were able to generate positive return on equity for shareholders over the past decade, which was marked by two major oil price downturns.

Overall FPSO supply and demand situation

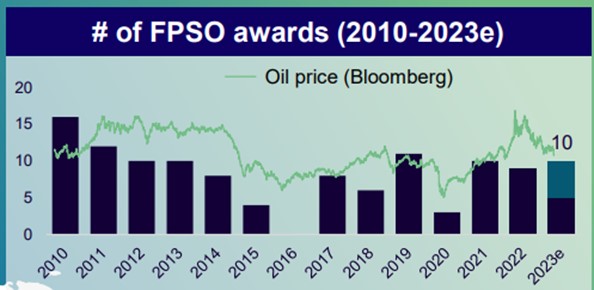

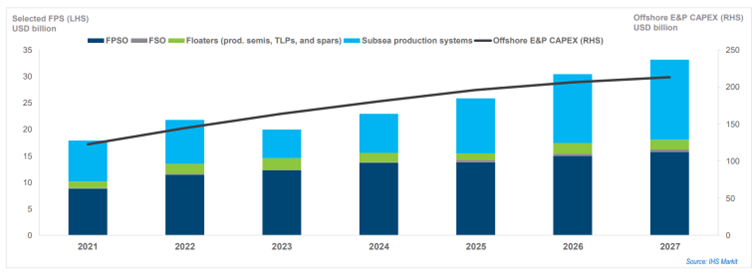

The global demand for FPSOs is around 8 to 10 units per year. About 40% to 50% of these units are chartered (leased), while the remaining are owned directly by oil companies.

It is widely known that many financial institutions have stopped lending to new upstream oil and gas projects due to ESG concern. Bankability is now a main constraint for most contractors, especially those with weak balance sheet and poor execution record.

Of the remaining 8 FPSO lease contractors, only 4 of them (SBM, Modec, BW and Yinson) have both the financing and engineering capacity to take on new jobs. (Yinson has the best track record for delivering projects on time.) The maximum number of FPSOs that this group of companies can take on per year is no more than 5. This is why there is often only 1 bidder (or a maximum of 2) for FPSO contracts nowadays.

Petrobras has postponed the deadline for submitting bids for a key FPSO to revitalize the Albacore field for several months to September 2023, due to insufficient bidders. This is the second time the it has postponed the bid, following an initial announcement in December 2022.

In any industry, when there is an undersupply then it is natural that the supplier has stronger bargaining power. This bargaining power is reflected in improving project IRR for lease contractor. Back in 2010-2014 period, the average IRR for FPSO lease contracts was around 13%. However, the recently awarded lease contracts are enjoying IRR of high teens now.

It is very difficult for a new entrant to enter FPSO business. This is because each FPSO job is very large (USD300m to USD3bn). It is very difficult to get financing without track record. In addition, clients are hesitant to entrust a new entrant with such a complex design and engineering job. They want to be sure that the project will be completed on time and within budget.

Now let’s look at the EPC side of the market. Oil companies tend to own 50% to 60% of the 8 to 10 units of FPSOs built each year and they would give the jobs to full EPC contractor. Full EPC here means the contractor will be responsible for the FEED, detail design engineering, sourcing, project management and construction. Most shipyards aren’t able to take full EPC jobs because it doesn’t have the FEED and detail design engineering capabilities to design an FPSO.

The leasing companies are not the only ones with a stacked backlog in this market. Many shipyards are also running close to the capacity.

According to CGS-CIMB’s channel checks, some EPC contractors/shipyard, i.e. Korean Hanwa Oceana and Hyundai Heavy Industries, are giving the full EPC tenders a miss, potentially due to their tight yard capacity and better margins from building LNG carriers. Italian Saipem (which won the FPSO P79 contract in 2021) is also not tendering for the Petrobras P84/P85 contracts, according to Upstream. It should be noted that all the big three Korean shipyards are filled up with lots of containerships and LNG carriers order. Topside integrator/EPC contractor such as Seatrium already has more than 10 large jobs in hand. Overall, the supply capacity EPC contractor is also tight.

Yinson – Top-tier FPSO lessor & operator in the world

Brief History

Yinson was founded in 1984 as a humble transport and logistics company in Johor Bahru, Malaysia. In 20 years, Yinson became one of Malaysia’s biggest transport companies, operating a fleet of 365 trucks and supplying a further 565 trucks to its customers.

The current CEO, Lim Chern Yuan, joined the company in 2005 as business development executive.

In 2010, Yinson expanded into marine transport with the acquisition of five tugboats. That same year, it won a contract for port cargo handling services in Vietnam.

In 2011, Yinson stepped foot into the oil and gas industry by forming a consortium with PetroVietnam Technical Services Corporation (PTSC, a subsidiary of PetroVietnam). The joint venture company was awarded a contract for the charter of a floating, storage, and offloading vessel (FSO), FSO PTSC Bien Dong 01. This paved the way for Yinson to win a contract for the charter of a floating, production, storage, and offloading vessel (FPSO), FPSO PTSC Lam Son.

In 2014, it acquired established Norwegian FPSO company, Fred. Olsen Production ASA (Fred), a company with deep expertise in FPSO design and build with a strategy for long-term charter contracts. Through the acquisition, Yinson inherited a strong and experienced team, as well as contracts for a further three FPSO vessels, and a mobile offshore production unit (MOPU).

The acquisition of Fred was done below the fair value of its net asset value and resulted in a bargain purchase of RM121m. Yinson paid a net cash of RM358m for Fred and disposed one of the three FPSOs and took back RM189m within a year from date of acquisition. They payback period for the acquisition of Fred is likely to be very short, but more importantly, the strong engineering team and track record of Fred propel Yinson a whole new level.

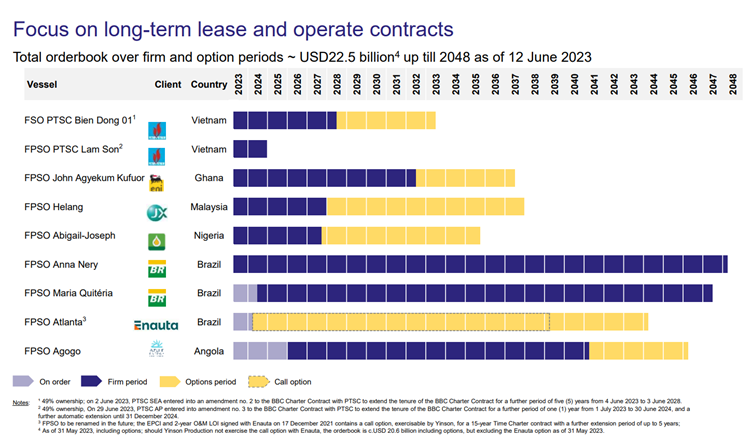

By mid-2016, Yinson divested its non-oil and gas businesses, streamlining the business to specifically serve the offshore oil and gas industry. Since the acquisition, it has added four new FPSO projects to its track record (FPSO JAK, Ghana; FPSO Helang, Malaysia; FPSO AJ, Nigeria and FPSO Anna Nery, Brazil). Its latest assets: FPSO Atlanta, Brazil; FPSO Maria Quiteria, Brazil; and FPSO Agogo, Angola are currently under construction. Today, with diversified geographical presence and extensive engineering and operational expertise, Yinson has grown to become one of the largest independent FPSO leasing companies globally.

Strategy

Yinson focuses on getting long-term charter contracts, which generate long-term revenue as opposed to EPCI jobs. Focusing on larger vessels with longer firm lease period naturally lowers the risk of termination. FPSO is essentially a floating factory which produces oil. For larger oil field, the average cash production cost per barrel is merely single digit U.S. dollars. All the exploration and subsea assets invested are sunk cost, thereby even if oil price dropped to USD30 per barrel, it still makes sense for the oil companies to run the floating factory since the variable cost is less than USD10 per barrel.

It also exercises discipline in selecting clients with strong financial positions. This strategy has helped Yinson weather the previous oil downturns in 2014 and 2020.

So how do they assess counter-party risk? For large oil companies, the test is if the banks are willing to fund the FPSO project on a non-recourse (to Yinson) basis. If the bank is happy with the taking the FPSO as collateral plus a corporate guarantee from the oil company, then it is considered a strong counterparty. For smaller oil companies, it is simple, Yinson basically do not take much credit risk, if any. They would only do a project if the client were willing to fund 100% of the CAPEX and agreed to conservatively written contractual terms. Let’s take a look at the following two examples:

- FPSO Atlanta (currently under construction):

Yinson negotiates with Enauta for a turnkey EPCI contract with an option to purchase the FPSO before the start of production. This improves capital efficiency while lowers the capital at risk, since conversion capex is fully funded by Enauta. Yinson would earn an EPCI margin. When it exercises the option, portion of the equity comes from the EPCI margin, and the debt is non-recourse to Yinson. The payback period on its equity is expected to be less than 3 years.

- FPSO Abigail-Joseph (upgraded from FPSO Knock Allan):

As mentioned, Knock Allan was terminated (with full compensation) and Yinson upgraded and redeployed it for First E&P to work in Nigeria. First E&P paid for the entire CAPEX, and Yinson is remains the owner of the vessel. The FPSO is currently leased to First E&P for a firm period of 7 years, with an optional period of 8 years.

Yinson also aims to maximize contractual protection and ensure the bankability of its projects. As mentioned in the previous section, Yinson was compensated for the termination of existing leases in two of the four cases, and for the termination of contracts for vessels under construction in the two other cases.

Given FPSO leasing is highly capital-intensive business, Yinson is open to exploring sensible sensible options to maximize capital efficiency. In 2017, it sold 26% stake in FPSO JAK to Japanese consortium, which allowed it to take back majority of its equity capital in the project. (Debt related to that FPSO is non-recourse.) It is also looking to further recycle capital from its operational projects to fund further growth in the near term.

Competitive Advantage

Founder-led management helps to impose discipline in turning down weak clients and focusing on conservatively written contractual terms.

Project management and execution – Yinson has the best track record in delivering project on time and within budget.

Progressive mindset and successful change management - Yinson has been working on improving its operational software with its vendor AVEVA. While competitors may also work with the same vendor to develop similar software, the hardest part is to implement change management. (You can have good software or improved processes but doesn’t mean employees willing to use it) We shouldn’t forget Fred Olsen was acquired only in 2014, it takes a lot of leadership, persuasion, and implementation to change the way people did things.

Integrated model as owner and operator of the FPSO. This allows Yinson to collect extensive data through operating and maintaining its FPSO, and then feedback these insights into the design process. Couple with continuous investment into R&D, it has been able to come up with better and better FPSO design. This is something that a pure EPC contractor / integrator yard cannot do.

On R&D front, Yinson and SBM are the only two FPSO operators in the world that have deployed the digital twin technology. A digital twin is a virtual model that represents the status of a real-world object in real-time. A digital twin of each FPSO vessel will be used to capture engineering and operational data through the complete asset lifecycle to improve visualisation, reliability, and efficiency. It will eventually allow them to automate many FPSO operations, optimising safety and operational performance greatly while lowering costs. Yinson is currently working with AVEVA to develop autonomous FPSO solution.

Yinson is also leading in the design of low-emission FPSO. This is important because emission reduction is a key priority for all oil majors.

Consistently profitable and bankability. A good track record attracts better projects, couple with strong financial performance, these helps Yinson to secure funding in current environment. As mentioned, financing capacity is scarce across the FPSO lease contractors in the world.

A niche in redeployment job. Redeployment means taking an existing FPSO, upgrading it and redeploying it to another field in a relative short span of time. This is not very common since FPSO is usually customized to a specific field. However, Yinson has delivered 2 redeployment jobs thus far (FPSO AJ and FPSO Helang) and is working on a third one (FPSO Atlanta). This is an added advantage which enables the company to be highly flexible, none of its main competitors are taking on such job.

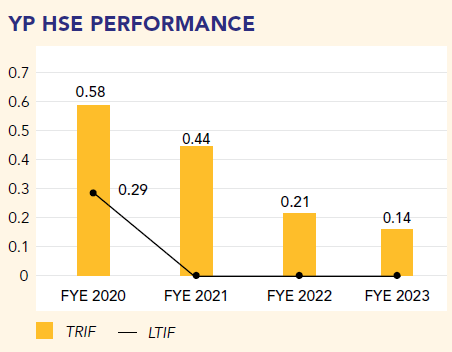

Health, safety and Environment (HSE) performance – Yinson has no major HSE incident thus far. It can be contributed to a strong safety culture, policy, extensive training programs and well design FPSO with sensor to monitor equipment performance. It achieves TRIF (*Total Recordable Injury Frequency) of 0.14 in FYE2023, well below industry benchmark of 0.90.

Source: Yinson annual report

TRIF’s calculation: The number of recordable incidents (fatalities + lost work day cases + restricted work day cases + medical treatment cases) per million hours worked.

LTIF = Lost Time Injury Frequency

Financial performance

Under finance lease accounting, the investment in CAPEX to construct the FPSO is recognized as contract asset on the balance sheet. The change in contract asset must be included in reported cash flow from operations. In reality, this change in contract asset represents CAPEX to build new FPSOs and should not be considered as operating cash flow. The actual operating cash generated for FY Jan23 should be RM1.36 bn.

Since 2012, Yinson generated cumulative net income to common stockholders of RM2.6 bn with an actual operating cash flow of RM5.3bn. It has returned RM0.84bn as dividend to common stockholders and bought back shares worth RM0.37bn. It also raised a total of RM2.2bn equity to fund the purchase of Fred Olsen as well as the latest project FPSO Agogo etc. The net equity raised from shareholders is RM1bn.

It also invested RM16.6bn mainly into building new FPSOs and recycled RM1.2bn through selling down stake in completed FPSOs and dividends from its JV. The net capital required to fund these projects are financed through RM8.4bn of debt and, RM1.76bn of perpetual securities and net equity issuance of RM1bn.

Free cash flow generation and gearing

FPSO Anna Nery achieved financial acceptance in May-23 and began generating lease income. Currently, it still has 3 more FPSOs under construction. FPSO Atlanta and FPSO Maria Quiteria will be delivered next year and FPSO Agogo will be delivered by Feb-26. Assuming Yinson does not take on new jobs and do not spend further CAPEX in the renewable energy division, its free cash flow generation should be more than RM3bn each year from FY Jan-27 onwards. This level of free cash flow generation should be sustainable for at least 15 years based on the firm lease period.

If perpetual securities are treated as debt, the current net gearing level stands at 2.1x and is likely to peak in the current financial year Jan-24. If no new jobs are taken, the net gearing level will begin to fall sharply to less than 1x in three years. While it is likely that Yinson would take on new jobs (which makes a lot of sense given the strong seller market now), we think the additional CAPEX needed could be funded through capital recycling and customers’ downpayment.

Recourse vs. non-recourse debt

As explained, after FPSO achieved final acceptance and release from its performance guarantee, the debt will become non-recourse to Yinson. As at 1Q FY Apr-23, 37% of debt is non-recourse and its composition should move up by end of the financial year as debt related to Anna Nery should become non-recourse soon.

While the current level of net gearing is on the high side, this is not unusual for infrastructure companies to have high gearing during construction phase before cash flow begins to come in. Given the nature of the firm contract, the real risk lies with project management and not so much about gearing.

Perpetual securities

There had been extensive debate on whether perpetual securities should be treated as debt or equity. In accordance with accounting principles, it is treated as equity because the company has no obligation to pay any distribution and has the option to elect for distribution deferment at its sole discretion, which does not constitute a breach of covenant. The perpetual securities may also be redeemed at the option of YTMC.

To us, our focus is to understand the actual cash flow that belongs to common stockholders, and we treat it as debt when we evaluate the company.

Renewable Energy and GreenTech

In 2019, Yinson diversified into renewables. Within a year, it acquired the first operational renewables asset, the 175MWp(DC) Bhadia solar plants in India, and built a strong pipeline of greenfield development projects across the globe. In early 2021, it secured a new contract to build, own and operate a 285MWp(DC) solar plant, which is currently under commissioning in the Nokh Solar Park, India. Unfortunately, the sudden surge in solar panel prices after the contract was awarded resulted in an impairment loss of RM117m recognized in FY Jan-23.

In 2020, Yinson established Yinson GreenTech. The unit focuses on investing in new technologies and business areas that enable the global transition to a low-carbon environment, through investments in marine, mobility, and energy segments. It aims to establish green technologies as a major revenue stream for Yinson and to develop profitable, disruptive businesses, based on clean technologies and digitalization.

In 2023, Yinson established Farosson to provide advisory, investment and asset management services in the area of sustainable infrastructure investing. Farosson will also assist Yinson in recycling the capital from its operational FPSOs assets. Potentially this could includes sell down, spin-off or “REIT-ing” of such assets.

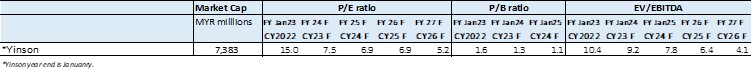

Valuation

The proper way to value an FPSO lessor & operation is to perform discounted cash flow to arrive at the net present value of the company. Given that all the sell side analysts have done extensive jobs on this, we would take a simpler approach to gauge the valuation.

The weighted average residual contract duration (WARCD) is 20.6 years, with a total contracted future revenue of maximum USD22.5bn. The WARCD concept is similar to the weighted average lease expiry (WALE) used in commercial real estate to measure the average length of leases for a property or portfolio of properties.

As we have shown, the actual operating cash flow should reach over RM3bn in calendar year 2026 and is sustainable for at least another 15 years based on firm period alone. This compared to market cap of RM7.4bn today with total net debt of RM11bn. The debt could be fully paid within a few years if the company does not take on new project. The cash leftover for shareholder may equal 5 to 8 times of today’s market cap.

Conventional P/E ratio valuation does not consider the duration of the recurring profits which, in this case could last 15 years or more. For those who are keen, the fully diluted P/E ratio of the company would hit 5.2x in FY Jan-27 after FPSO Agogo becomes operational. This does not take into account any new jobs that might come in from now until then.

Summary

To quote Yinson’s CEO Lim Chern Yuan from the edge article:

“We have never been in such a good position to negotiate contracts, with our order book, we are looking at closer to a billion dollars of Ebitda by 2025, 2026.”

Yinson is one of the few reputable FPSO lease contractors and operators who have both the financing capacity and project execution track record. This allows them to exercise significant bargaining power in a seller’s market. There are no credible new entrants to this market yet, and the current seller’s market is likely to continue for at least a few years unless oil prices decline significantly. The good news is that FPSO leasing contracts are long-term, so once they are signed, they generate recurring revenue with a good rate of return for 15-25 years.

In a recent example, Yinson was the only bidder for the FPSO Maria Quiteria project (Parque das Baleias field) twice in a row, but the tender was cancelled each time. The project’s original tender was launched back in 2019, with Yinson being the only qualified bidder. Subsequently, last year, Petrobras had opted to do a rebidding on the project, in hopes of inducing more bidding competition in pursuit of better pricing. Nevertheless, the rebidding yielded no different result as YINSON once again emerged as its sole bidder. In the end, Petrobras awarded the job to Yinson through direct negotiation.

As per what we spell out in our investment philosophy, it is the jockey that matters. The management team led by Lim Chern Yuan is what creates the differentiations between Yinson and its competitors over the years. As a minority shareholder, we rely on management to run the business well to generate cash flow. Equally important is the integrity and capability of the management in allocating the capital earned from business. We are counting on them to channel these cash flow either back to us or to further reinvest in the business if it makes economic sense and improve ROE. In the last decade where we have been monitoring Yinson, the management has consistently shown high levels of transparency, accountability, fairness, and capital discipline. The company would also actively be buying back its shares when it is clearly the most compelling action to do.

Yinson is now among the top-tier FPSO lessor & operator in the world. As it continues to maintain excellent execution track record. investing in R&D towards fully autonomous FPSOs, and potentially moves into designing and building of new hull in the future, it could become the best FPSO player in the world in the coming decade.

This article would not have been possible without the sharing of Raymond Yap of CGSCIMB and Keat Seng of KSC.

Appendix

FPSO lease contractor market back in 2011

source: Fred Olsen Production's slide

source: Fred Olsen Production's slide

FPSO/FSO & TLP Market Trends as of 2022

FPSO awards v.s. oil price

Offshore E&P CAPEX forecast

Notes and Disclaimers

This essay and the information contained herein is not a specific offer of products or services. Information on this essay is not an offer to buy or sell, or a solicitation of any offer to buy or sell the securities mentioned herein.

Oaklands Path may be long or short the securities mentioned herein and has no duty or obligation to disclose or update our action on these securities.

This essay contains information and views as of the date indicated and such information and views are subject to change without notice. We have no duty or obligation to update the information contained herein. Further, we make no representation, and it should not be assumed, that past investment performance is an indication of future results. Moreover, wherever there is the potential for profit there is also the possibility of loss.

Certain information contained herein concerning economic trends and performance is based on or derived from information provided by independent third-party sources. Although we obtain information contained in our newsletter from sources we believe to be reliable, we cannot guarantee its accuracy. Moreover, independent third-party sources cited in these materials are not making any representations or warranties regarding any information attributed to them and shall have no liability in connection with the use of such information in these materials.